It’s no secret that extremist groups like al-Qaeda and ISIL use the American prison at Guantánamo Bay as a recruiting tool and rallying cry against the United States. The topic has come up often in Washington, with both President George W. Bush and President Barack Obama acknowledging its use by jihadist groups. In congressional hearings, the issue is raised frequently, with members on both sides of the aisle addressing the detention facility’s use in enemy propaganda. But these statements tend to be superficial. Few of these discussions touch on how the prison is invoked, how often, and whether closing Guantánamo would have a significant effect on its propaganda use. When these aspects are addressed, they are frequently downplayed or addressed skeptically, without reference to solid empirical evidence. The available data, which I discuss below, show that the symbol of Guantánamo remains a significant device in extremists’ messaging, portrayed as an instrument of an American war on Islam.

Skeptics of the propagandist utility of the prison have included terrorism analysts, commentators, lawmakers, and, unsurprisingly, former-Vice President Dick Cheney. Mr. Cheney told an audience at the American Enterprise Institute in 2009 that the idea of Guantánamo being a propaganda and recruiting tool for al-Qaeda was just “another version of that same old refrain from the Left, ‘We brought it on ourselves,’” and in his memoirs Cheney wrote that he didn’t “have much sympathy for the view that we should find an alternative to Guantánamo … simply because we are worried about how we are perceived abroad.”

More recently, in a February Senate hearing on Guantánamo, Senator Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) railed against the idea that US actions affect jihadist motivations, saying, “Islamic terrorists don’t need an excuse to attack the United States. They don’t attack us for what we do, they attack us for who we are.”

But human rights abuses committed at Guantánamo (and other American detention sites) have come back to directly haunt the United States, most recently used by ISIL. Some critics, such as Cody Poplin and Sebastian Brady at Lawfare, seem unconvinced that the orange jumpsuits which have become ISIL’s garb for its prisoners have much to do with Guantánamo, and doubt the prison’s utility for the group’s propaganda generally. But if we look at ISIL’s use of the prison in word and deed, a different picture emerges — that of the group taking US human rights abuses as its own tactics. Not only does ISIL refer to Guantánamo in multiple issues of Dabiq (ISIL’s online English-language magazine), it has also reportedly waterboarded prisoners, and has reportedly modeled its prison for Western hostages after the U.S. facility. It also explicitly included Guantánamo in the statement delivered by American hostage Steven Sotloff in his execution video. This deliberate, targeted use of the American prison speaks volumes about the site’s continued propaganda utility to jihadist groups.

Nevertheless, Poplin and Brady argue that because Guantánamo is used less frequently than other topics in jihadist propaganda, it is unimportant to the propaganda effort. Thomas Joscelyn made a similar claim in 2010, noting that “al Qaeda is far more interested in other themes.” While they are correct that other issues are raised more than Guantánamo, they fail to adequately address the rationale behind the use of Guantánamo. The main purpose of al-Qaeda’s propaganda is to spread the myth of a Western war on Islam — to convince the group’s audience that a crusade led by the United States exists and that it threatens the worldwide Muslim community (ummah). If jihadist groups can convince the ummah that a Western war on Islam exists, it not only provides rationalization for their violent actions (playing on the Muslim obligation to defend the faith), but also keeps communities from supporting US efforts in the Muslim world and can turn ambivalent partners and populations into enemies. Guantánamo, and the abuses that the prison has come to symbolize, is used to feed that narrative in a very deliberate way.

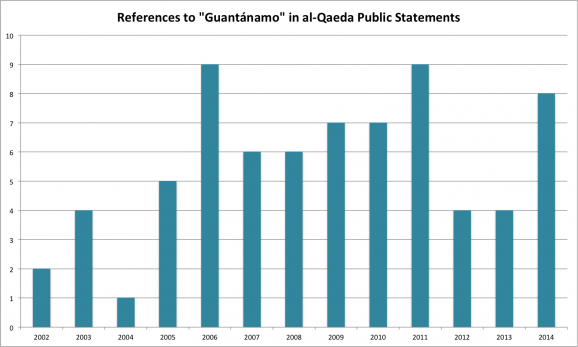

I have examined 72 examples of al-Qaeda and its affiliates using Guantánamo in their propaganda since 2002 (using Haverford College’s Al Qaeda Statements Index and other sources), and have coded this data according to how these groups use the prison in each statement. By far, the most common use of the prison is to bolster the idea of a Western war on the Muslim world. Even when al-Qaeda statements are not explicitly related to this narrative, they indirectly support that frame.

Poplin and Brady contend that the use of Guantánamo in jihadist propaganda is declining. Analyst Max Abrahms agrees. But this is also not borne out by the data. In the 72 statements from al-Qaeda and its affiliates (not including ISIL statements) mentioned above, the breakdown on Guantánamo references is as follows:

Though there was an observable reduction in 2012-2013, it was not a strong enough deviation for it to be interpreted as an overall trend towards reduction, especially given the uptick in 2014.

Not only do we have significant evidence of the use of Guantánamo in extremists’ efforts to recruit and mobilize individuals—we also have evidence of those messages’ success within the relevant audience. This propaganda has an effect on the battlefield. Former American military and intelligence officials have repeatedly told of the detention facility’s power as a motivator for waging war against US forces. “I learned in Iraq that the No. 1 reason foreign fighters flocked there to fight were the abuses carried out at Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo,” wrote former US Air Force interrogator Matthew Alexander in 2008.Another argument against the importance of Guantánamo in al-Qaeda and ISIL propaganda infers that even if Guantánamo is closed, it would not diminish use of the prison in propaganda.

Ben Wittes, writing in 2010, expressed these doubts, betting that closing the prison without freeing the detainees would not have much effect on the prison’s propaganda utility. But, a review of the Haverford College collection does not support this claim. I examined 38 mentions of the Abu Ghraib prison abuse scandal by al-Qaeda, its affiliates, and ISIL from 2004 to 2013. Mentions of the Iraqi prison in propaganda peaked in 2005, the year after the scandal broke.

Within this data set, Al-Qaeda in Iraq and the Islamic State of Iraq (ISIL’s predecessors) propaganda also reveals a trend that contradicts the assumption that jihadists would continue to frequently use Guantánamo as a talking point after it closes. The number of Abu Ghraib mentions by al-Qaeda in Iraq/the Islamic State of Iraq actually dropped as time progressed, and the only two mentions in statements from ISIL in 2013 are completely unrelated to the US prison scandal.

More evidence can be found when looking at ISIL’s Dabiq. Its nine issues contain no reference to Abu Ghraib at all.

Based on all of this, it seems that the United States’ handing Abu Ghraib over to Iraqi government control in 2006 has in fact lessened the prison’s propaganda utility for terrorist groups, even those inside Iraq, for whom it would presumably hold the most utility. The assumption that closing Guantánamo would likely not affect its use in terrorist propaganda therefore seems unfounded.

The study of how enemies exploit US human rights abuses in their propaganda is a sadly understudied field. Some, like Cheney and Senator Cotton contend it doesn’t matter. But part of our fight against al-Qaeda, its affiliates, and ISIL is a war of ideas. Clearly, the United States and its use of Guantánamo are not to blame for the actions of jihadist groups. Their actions are their own. But if these groups can convince their audience that the West (especially the United States) is waging a war against the Muslim world, this rationalizes their violent methods and delegitimizes American geopolitical and counterterrorism efforts. Guantánamo is used as a symbol of American abuses to bolster this narrative. Shuttering the prison down would go a long way toward refuting it.

For more on how al-Qaeda, its affiliates, and ISIL’s use of Guantánamo in their propaganda, Human Rights First has created a timeline of the most relevant examples, which you can find here.